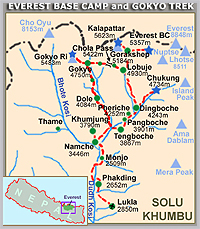

Remember when I complained about how cold I was on the Everest trail? You know, when it was so frigid that I wasn't sure if my fingers and toes were still attached to my body? Yeah, neither do I.

India. The name alone conjures many images: teeming, overcrowded cities, blisteringly hot temperatures, widespread poverty, unceasing chaos in the desperate daily lives of many of its inhabitants. (Oh, did I mention that it's really hot?)

Although it should be fairly obvious from the preceding bad-authory paragraph, I made it to India. After spending nearly a week in Kathmandu (and its abominable air), I jumped on my Jet Airways chariot, suffered through the first thirty minutes of Four Christmases (a Vince Vaughn-Reese Witherspoon effort that appeared well on its way to being a train wreck), and somehow convinced the Indian immigration authorities that I wasn't a terrorist. In other words, I flew to Delhi last Monday.

I must admit that I was a tad apprehensive about venturing to India when I initially constructed my itinerary back in January. I know it sounds crass, but India just seemed a lot "scarier" than Thailand and Nepal. I was 99.9% sure that I would either contract a life-threatening disease or be held hostage in some sort of India-Pakistan missile standoff. (My pessimism rears its ugly head once again. For those concerned, I have avoided both illness and imprisonment...so far.) Despite my self-calculated .1% chance of a debacle-free trip, I went ahead and signed up for four weeks of vegetarianism and 90 degree days. (By the way, I am suffering most from the lack of red meat in my diet. At this point, I anticipate eating steak or cheeseburgers for 27 consecutive meals when I return home.)

After arriving in Delhi, I was shuttled to the hostel that would be housing us for the first evening. Despite my fairly extensive travels, this was my first overnight stay at a youth hostel. (In the past, I have always opted for crummy "hotels" over hostels.) My mother is well-versed in the hostel circuit, having meandered through Europe in the 1960s with little money, and I recall her telling me that they were loads of fun because they allowed you to meet other young travelers. To her credit, youth hostels do allow one to converse with new contemporaries...unless you are rooming with five middle-aged Indian men and a German fellow who may be dead. (I eventually confirmed that the man from Deutschland was alive. He wasn't doing much besides lying face down on his bed, but he was breathing. Which was good because I don't think I would particularly enjoy sharing a room with a corpse.)

I won't elaborate on the restless night that I spent within the dank confines of the International Youth Hostel. All you need to know is that the low point was at 3 A.M. when a particularly foul-smelling gentleman lofted himself onto the upper level of our rickety set of bunk beds and I feared being crushed in a heap of wood, rusty nails, and my new roommate's pudgy torso. (Needless to say, I have determined that this will be my first and last foray into the wonderful world of youth hostels.)

After dining with two other volunteers at Side Wok (a too cleverly named Japanese restaurant that evidently was the only dining option within walking distance of the hostel), our group convened the next morning for a long day of sightseeing in the Indian capital. Cruising through the heavily congested streets in our "air-conditioned" taxi, we visited India Gate, Red Fort, Humayun's Tomb, and the Lotus Temple. For your viewing pleasure, a photo of each sight can be seen below. (Gallery note: The third and fourth photos are both from Humayun's Tomb. The third image is the actual tomb of Humayun, the Mughal Emperor, and the fourth image is the resting place of Ali Isa Khan Niyazi, a Mughal noble in the court of Sher Shah. Just in case you were really curious.)

The streets of Delhi were smelly, dirty, and brimming with people who spoke just a bit too much English. Touts (the sidewalk patrollers who claim to sell pretty much anything) in Kathmandu only knew enough of my native jive to engage me momentarily, but the Delhi hustlers were more persistent in their hawking. For example, I was everyone's "friend." "Come friend," "Hello friend," "Over here friend," "Just a look friend; good price." Although the fawning was incredibly flattering, my "friendships" ended as abruptly as they had begun when I refused to purchase their wares. "No, I don't need a drum." "No, I don't need a cigarette holder." "No, I don't need a used hair trimmer." "Why the hell would I need a badminton racket?"

After an exhausting day of touring Delhi and sidestepping merchants, we made our way to the Old Delhi Train Station for an overnight journey to Jodhpur. Although I was fairly certain that the ride would be lengthy, pungent, and uncomfortable, I was excited to witness the unique chaos of Indian public transportation. Since merely walking down the street provided many an absurd scene, I reasoned that a 12-hour train ride had to be even more ridiculous. And more debilitating to my overall health. (I was decidedly less excited about the latter.)

We boarded our assigned fleet of sleeper cars after a late dinner at a station restaurant that may or may not have been inspected for health code violations during the last century. (That's the slightly anal, Purell-using American talking; for all I know, this particular dining establishment may have been in line with India's health code. India's health code. To me, that's like the minimum SAT score needed to attend a big-time Division I school on a basketball scholarship. Just because you met the baseline requirement doesn't mean you should be trusted blindly. I think this makes sense, but I'm not positive. Let's just move on.)

As I lugged my bulging rucksack onto the train with the eyes of many an Indian focused squarely on my sweaty face, I was more conscious of the staring that has become fairly routine during my time in Asia. Now, I am used to being ogled (just ask the ladi...sorry, I'll stop), but I became slightly unsettled when a portly fellow, who appeared to only contribute burps to the conversation he was having with his seatmates, entered hour two of his attempt to stare at me for the entire evening. To alleviate my discomfort, I scampered up the first two levels of the fold-down bunks and tried to get some sleep. In retrospect, my decision to take the top cot was not a wise one. The perch offered little in the way of air movement or head space and I was slightly worried about breaking several bones should I tumble off my elevated resting place during the night.

Little did I know that the slim possibility of me falling out of bed would be the least of my concerns. Despite the stuffiness of my upper deck sleeping quarter, I managed to pass out for a while. A few hours later, I woke up with a sharp, unpleasant twinge in my chest. As you might remember, I suffered discomfort in the same area of my body while doggedly pursuing the summit of Kala Pattar. You also might remember that KP was a towering mountain. However, I was now having more excruciating pain...while reclining on a train. (I know that my incessant complaining gives the impression that I have the pain tolerance of five-year old girl, but this was one of the worst pains-and there have been a few-that I've ever experienced. In fact, I would have told a doctor that, on a 1 to 10 scale, the pain was an 11. So there.)

After a few minutes of futilely trying to temper the sharp pang in my upper torso, I became somewhat disconcerted about the situation at hand. I was lying in the sticky sleeper compartment of a rickety boxcar. I was 3 hours into an overnight jaunt through the barren Indian desert. My chest felt like it might cave in. Sleep was an impossibility. Oh, and I was also having difficulty breathing.

My troubles began in Nepal when I picked up a slight bout of "Kathmandu cough." Despite its cute little nickname, it's a nasty condition that is caused by inhaling the Nepali capital's disgusting smog for extended periods of time. Ohhh, so that's why everyone wears surgical masks all day. When I boarded the crowded train in Delhi, I thought that my cough would be merely an annoyance during the night. Not so. After 15 minutes of lying in agony and listening to the shrill cries of "Chai!" as the tea man made his rounds, I was fairly confident that one of my lungs had collapsed. (Such an overreaction shouldn't come as a surprise since I think that I have contracted mononucleosis any time my throat hurts.) In fact, my pathetic wheezing probably could have landed me a starring role in the next Vicks VapoRub commercial. (I'll keep you posted if anything develops on that front.) Since I've whined enough about my chest pain, I offer this brief summary of the next nine hours: My breathing sounded like that of an emphysema patient and I slept for approximately 27 minutes during that time period. Fantastic.

When our posse arrived in Jodhpur, I managed to stumble off the train without being overwhelmed by my massive backpack and kept the whimpering to a minimum. (Way to go, me.) The sun was shining, the long trip was over, and we were on our way to rest up at a local hotel. Things weren't that bad. (The previous was, of course, meant to be sarcastic. Things were actually pretty awful. However, I did have some cause for optimism since I managed to avoid dying within the decrepit confines of an Indian sleeper car. As I've mentioned before, merely surviving journeys on public transportation in Asia is reason enough for a rose-colored worldview.)

After several rickshaw drivers nearly came to blows during a spat over who would get our precious rupees, we collapsed at our lodgings for some much-needed rest. A doctor was summoned and, after looking me over for a mere thirty seconds, he diagnosed me with a "viral." Although he was unsure of which specific "viral" had invaded my body, he assured me that I was not terminal and shouldn't worry about arranging a final Skype call to my family. Crisis averted. (I was dubious of his assessment. Of course.) Anyway, he told me to purchase the whole right side of the pharmacy (read: 4 different pills and a bottle of cough syrup) and, lo and behold, I felt better the next day. Well, a little better. Despite my improvement, I know that he didn't recommend riding a camel around the Ossian desert...